On the face of it, the private sector’s transformation track record is underwhelming. While there has been some progress, its pace is slow. However, the Department of Labour’s heavy-handed approach is misguided and likely to be ineffective. Only two companies in the entire country meet gazetted targets.

According to the latest Commission for Employment Equity report published by the Department of Labour, 65% of top managers in the private sector are white with just 14% African. Likewise for senior managers, 51% are white and 21% African. There has been some, but not much improvement over the past years. According to the 2015/16 report of the Commission for Employment Equity, 72.4% of the 53 639 top managers in the private sector were white while 10.8% were African. Of the 117 238 senior managers in the private sector, 64% were white while 15% were African.

The report benchmarks this against an economically active population of 25 million, 81% of whom are African. Of course, top managers are not drawn from the broader pool of economically active South Africans, a third of whom are unemployed. Rather, they are likely to come from a narrow base of highly educated, experienced workers. We can surmise that top managers of entities that employ 50+ employees are likely to have some tertiary education and are probably going to be over 35. In that cohort of just over 2.2 million South Africans, 30% are white while 59% are black. Even against that benchmark, we still have a way to go.

In light of this data, it is not terribly surprising that the Department of Labour has drawn the conclusion that the existing approach is too timid. But the Department’s dirigiste remedy, with industry-specific targets for designated male and female employees in skilled, middle management / professional and senior and top management occupation levels is an overreach. Failure to comply with the new directives could result in fines of up to 10% of turnover, and the consequences for individual firms and the economy could be devastating.

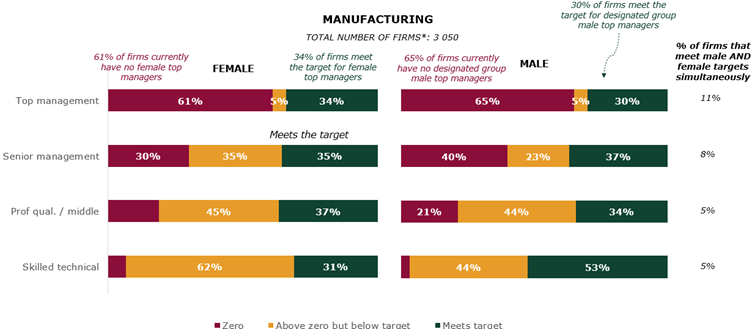

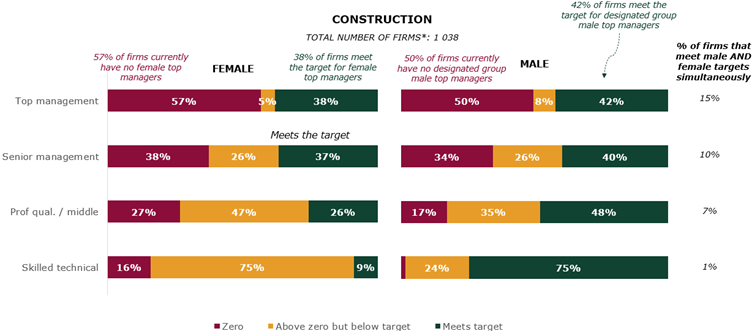

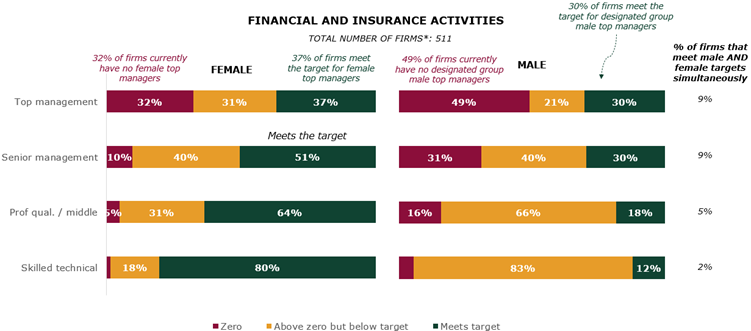

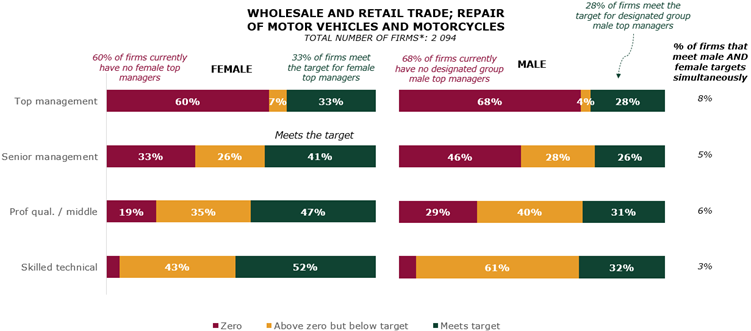

On the face of it, at a sector level some of the targets look doable. However, it is not the sector that needs to comply, but the individual firm. We have therefore used firm level data from the Employment Equity Commission to determine how many private sector firms in South Africa currently meet these targets. The answer is shocking. Of the 14 033 private sector companies with 50 or more employees who reported to the EE Commission in 2023, only two companies in the whole country met the target – a media and signage company and a liquor distributor. While several companies meet some gender or population group targets at some occupation levels, the challenge is meeting gender and population group targets at all levels at the same time.

Take the Construction Sector where not one of the 1 038 designated private firms meets the target. While 42% of firms meet the target for designated men in top management, and 38% of firms meet the target for women in top management just 15% of firms meet the target for both. Lower down at the skilled technical level, 75% of firms meet the target for designated men. But only a paltry 9% of firms meet the target for women. Just 1% of firms meet the combined target for men and women in that occupation. Assuming limited growth in headcount, to meet sector targets the Construction Sector will need to shed previously disadvantaged male skilled technical employees to make way for women, including white women, who, in an astonishing twist of bureaucratic logic, now count as a “designated” group. If such candidates even exist in sufficient numbers, the outcome would be nothing short of absurd: a policy aimed at correcting racial inequality ends up sidelining black men while elevating white women.